This is another guest posting by Jim Lynch, our favorite English teacher from Bishop O’Reilly. I still remember reading this book in 1974 as one of our class assignments. I just purchased the Kindle version and I’m planning to re-read it on an upcoming vacation.

This is another guest posting by Jim Lynch, our favorite English teacher from Bishop O’Reilly. I still remember reading this book in 1974 as one of our class assignments. I just purchased the Kindle version and I’m planning to re-read it on an upcoming vacation.

The Golding Rule

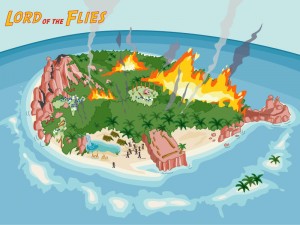

One of the standard assignments in my high school British Literature curriculum was William Golding’s Lord of the Flies. Written in 1954, the novel concerns a group of pre-adolescent English boys stranded on a tropical island without adults, after an abortive attempt to evacuate them to safety during a nuclear war. Within a brief period of time, these children of a sophisticated Western European nation with a proud tradition of culture and civilization turn to bloodlust, savagery and murder.

After the classes finished an exhaustive discussion of the novel, I always called for a personal and secret written response to a few pointed questions. On scraps of paper they’d respond to the following: 1. If you and your entire class were stranded on a similar uncharted island for the rest of your lives, without hope of rescue, name the person in the class for whom you would vote to be chief. 2. Excluding identification, is there any potential Jack Merridew (the antagonist who become a bloody dictator) in the class? 3. Without rescue, would the eventual outcome your stay on the island be positive or negative?

Invariably, their responses led me to wonder if we had read the same book. In their eighteen-year-old naive camaraderie, an overwhelming majority of my students: 1. Named a popular athlete or student council president as chief, 2. Refused to allow for the possibility that any of their peers could become ruthless savages, and 3. Thought that their acquired wisdom would allow them to overcome and solve any difficulties that arose. “Gilligan’s Island” anyone?

After each and every such class response, I’d attempt to bring my students’ utopian vision more in line with Golding’s theme. In the summer of 1972, I reminded them, Tropical Storm Agnes wrought devastation to the town surrounding the very school in which they now sat. Many of my students were evacuated from the flood zone. After the Susquehanna’s raging waters finally subsided, I rode through the town in a panel truck, picking up flat tires from huge pay-loaders and delivering repaired ones, as an employee of a local tire company.

On every street corner, I’d continue to point out, were members of the National Guard carrying locked and loaded M-16’s, with orders to shoot looters on sight. Pennsylvania’s governor had declared a state of emergency, and the local police force was temporarily out of commission. Why would such an action be necessary in such an area filled with friendly family neighborhoods and small businesses? What could have been the governor’s reasons for such a move? After moments of silence, the only response ever offered was a variation of, “That was different.”

I then would offer a theoretical proposition. Suppose, I said, representatives of the police in their municipality had gone on the local news and indicated that protracted and unsuccessful negotiations for a new contract had broken down. Consequently, all members of the police department would go on strike as of midnight next Friday. Would the crime rate in their town, I asked, go up, go down or remain the same on that weekend? Once again I encountered initial silence, followed by, “That’s different.”

Reminding them that Golding crafted his story as a microcosm of larger society, I then asked why their parents paid hefty taxes to support a criminal justice system. Beyond police protection, I said, why do we need courthouses, magistrates, judges, lawyers, and prison facilities? Because there are bad people in society, they would respond, and we have to protect ourselves from them. And all those bad people, I’d remind them, once sat in classes just like this one and had every opportunity to work hard, play by the rules, and choose happy and productive lives.

Ultimately, I would conclude class discussions of the book with my hope that my students would reopen the discussion at their 25th class reunion, and my belief that, by that time, the seeds planted in their consciousness by Golding would have germinated in the soil of their maturity. While I appreciated their idealism, I found their naivete unsettling. I only attended one such class reunion, but the alumni were having such a memorable evening catching up and sharing family photos that I was loath to raise the issue with anyone.

I seriously doubt, however, that the needle would have moved to a great degree in the direction of a pessimistic view of the human condition. While the signs are abundant, most prefer to avert their eyes and focus on family and friends, rather than the larger world. Despite media websites, and twenty-four-hour cable news, people tend to push unpleasant intrusions into the background.

Iran’s hell-bent quest for atomic weapons; Russia’s incursions into the Ukraine; ISIS’s mass beheading, burning and drowning, and its goal of a world-wide caliphate; domestic terrorism; a $19 trillion national debt with 93 million American adults unemployed; massive illegal immigration; race riots in St. Louis and Baltimore; soaring homicide rates in urban areas – let the people we elected deal with such things, while we are busy attending to our own problems. When it appears that crime is a little too close for comfort, we’ll simply have an ADT sign planted in our front yard and a deadbolt installed on our front door.

Most people believe that if we live by the golden rule, we’ll all get along. And for those few in society who don’t abide by that principle, we have police departments and a criminal justice system. The ugly reality that we don’t want to face, however, is that only a larger framework of laws makes it possible for anyone to abide by such an idealistic rule. For those who choose to live by a more primitive code of behavior, the golden rule is a fairy tale.

People likely to ignore criminal law are only restrained by the penalties involved in breaking the law. When the laws cannot be enforced due to natural or man-made disasters, all bets are off, and the ranks of those few begin to swell. According to historian Will Durant, “Pugnacity, brutality, greed, and sexual readiness were advantages in the struggle for existence.” Those “relics” of our emergence as a species, he cautions, are still firmly embedded in our DNA. The systems of laws that have evolved over millennia were put in place to protect us from ourselves.

While most us are focused on mortgages, soccer practice for the kids and paying the bills, however, those laws are beginning to fray around the edges, along with many commonly held social mores and practices. As the federal government looks the other way in the face of millions of illegal immigrants streaming across our southern border, and of mayors establishing sanctuary cities in defiance of federal law, society has also changed its views on acceptable behavior. The melting pot has been replaced by separate, “multi-cultural” groups with individual agendas.

Even when people do venture outside their home and work bubbles to offer an opinion on larger issues, they are subject to censure for being politically incorrect. They aren’t successful because they have invested time and energy in education and career, but because of their “white privilege” (African-American success is often attributed to being an “Uncle Tom”). In the absurdity of political correctness, domestic Islamist terrorism has been transformed into workplace violence, illegal immigrants have become undocumented immigrants, drug addicts are dubbed chemically-challenged, prostitutes are renamed sex workers, and an illegitimate baby becomes a love child.

On many university campuses, students are warned about “micro-aggressions” for using “trigger words” which remind the hearer of past traumatic events: “Selling someone down the river” is a racist reference to slavery; acting like a “hooligan” and being put into a “Paddy Wagon” are slur terms for those of Irish ethnicity; calling a rioter and looter a “thug” is code terminology for the “N word.” If you have doubts about man’s role in climate change, you are branded a “global warming denier” (with the added insinuation echoing a holocaust denier). Charlton Heston aptly referred to political correctness as “tyranny with manners.”

Durant’s comment on this phenomenon is instructive: “Civilization gives way to confrontation; law yields to minority force; marriage becomes a short-term investment in diversified insecurities; reproduction is left to mishaps and misfits; and the fertility of incompetence breeds from the bottom while the sterility of intelligence lets the race wither at the top.”

What too many fail to recognize or acknowledge in the sophisticated, technologically-advanced 21st century is that civilization is a razor-thin veneer. Despite our scientific discoveries and breakthroughs, we remain captives of our primitive ancestors in our essential nature. Man is only an evolutionary link between primitive apes and truly civilized human beings.

Having served in the Royal Navy during World War II, Golding witnessed the worst of human behavior, with the cost of more than 60 million dead – six million of whom were cruelly obliterated in the concentration camps of a cultured and Christian European state. The trauma he witnessed occurred a mere twenty years after the seemingly minor and avoidable events leading to the outbreak of World War I, which claimed 37 million military and civilian casualties.

Golding knew that those civilized British children in his novel represent the distressing reality about where humankind actually stands in its slow development as a species. Through his work, he speaks to the necessary, if unpleasant, fact that the golden rule is only possible within the context of the Golding rule: we must never fail to recognize and remember that civilization is built on the rule of law. Treating one another with generosity, kindness and decency is contingent upon our willingness to subordinate ourselves to the hard-won lessons of history. Without that commitment, we run the horrific risk of setting, not an island, but the world on fire.

Jim Lynch

Fleetwood, PA

August 2, 2015

————–

If you’d like to provide any feedback to Mr. Lynch, he can be reached at jimadalynch(at)gmail.com. You’ll need to fix that email to use it, by substituting the @ symbol for the (at) characters.