Because I’m a pilot, I often get asked to speculate on the causes of plane crashes where there’s not enough evidence to know for sure what really happened. Such is the case with Steve Fossett where I get periodic requests to give my opinion about what happened in his mysterious disappearance in a borrowed airplane. Just for those who haven’t been paying attention, Steve Fossett was a wealthy adventurer who set numerous aviation records including traveling around the world solo in a balloon as well as flying an airplane solo without refueling around the world. He took off on a sightseeing flight from Barron Hilton’s Ranch in Nevada last September and was never seen again. Just a few weeks ago, more than a year after he disappeared, some of his personal effects were found by a hiker about 80 miles from the ranch where he had departed. Shortly after that, the crash site was discovered in the Sierra Nevada mountains.

A recent Avweb newsletter linked a set of pictures on Flickr posted by one of the SAR team members who helped clean up Steve Fossett’s crash site. There are about 10 pictures in the middle that show parts of the plane that start right around the one with the newspaper clipping image.

What I found interesting was the caption on the photo 43 that mentioned that the plane impacted the ground climbing at about a 10 degree angle on a slope that was at a 20 degree angle leading me to think that Fossett may have had a problem with the airplane and so he tried to land by attempting to climb uphill and get the aircraft to stall right around the time it contacted the ground. A ‘roll out’, if you want to call it that, on a 20 degree slope uphill would be pretty short. However, there were a lot of rocks and trees and so it appears that the plane broke apart on landing and then was consumed by fire. To make that maneuver work, you would have to do it ‘just right’.

At an EAA chapter meeting last night, someone mentioned that Bob Hoover performed this maneuver where he knew he was going to crash and so he did it going up hill and he and his passengers walked away from it. Here’s that story, excerpted from my (autographed) copy of Bob Hoover’s autobiographical book “Forever Flying”.

One of the more frightening experiences I’ve had occurred after an air show in 1989 at San Diego. It was held at Brown Field, which is located just a few miles from the Mexican border.

I had completed my performances in the P-51 and the Shrike Commander. I told the line boy who drove the fuel truck to service the Shrike quickly so I could leave right after the show was completed.

The young man asked how much fuel I needed. I told him I wanted precisely sixty gallons. I added, “That’s hundred octane.”

After my performance, I went to the manager’s office, where he received a phone call from the same young man. The manager told me the boy wanted to know if 100 LL (low lead) was all right for my airplane. I told him it was. He relayed the message.

Normally I like to be present when the airplane is being serviced, but I was held up when I came out of the airport manager’s office. By the time I got to the airplane, the truck was pulling away. I said, “Fueling done?” The boy replied, “Yes, sir. It was sixty gallons precisely.”

When I taxied out, probably at least a hundred airplanes were waiting for takeoff. But as soon as I called in, the tower said, “Mr. Hoover, we want you to taxi to the head of the line.”

I did not like to leapfrog ahead of other pilots. However, since time was scarce that day for me and my two passengers, I accepted the tower’s kind offer.

The takeoff was smooth. Everything was normal and checked out perfectly. All of a sudden, at about three hundred feet, I realized I didn’t have any power in the Shrike. I started losing airspeed.

I dumped the nose, but I couldn’t understand what was happening. Everything checked out. The manifold pressure was right where it was supposed to be. The rpm were at the right setting. The fuel pressure and oil pressure were in good shape. Even though the gauges indicated that nothing was wrong, I knew something was. I started looking for a place to land. That would not be easy.

Brown Field is located on a plateau. To the north where I was headed, there were deep ravines. I could try to recover and head back to the airport, but I knew I wouldn’t make it.

My two passengers tried to remain calm, but they were obviously frightened. Both thought we were going to crash and die. “Mr. Hoover,” they asked more than once, “are we going to make it?” I assured them we would.

As I have mentioned before, each time potential disaster strikes, I rely on my experience of anticipating trouble to help me out. I had flown the P-51 cross-country for many years. I’d often considered what might happen if I had to put it down over the Rockies.

Recalling those thoughts, I dumped the nose of the Shrike. I kept my best glide speed until I reached the very end of the ravine. Landing in the bottom of the canyon meant no survival. Our only chance was to pull up and land on the side of the ravine.

As my airspeed bled off, I dropped the landing gear and flaps. I wanted to be at a minimum forward speed on impact. The landing gear would cushion the impact along with the tires and struts before the impact hit us square on.

I was down in a V-shaped ravine. A thousand feet wide at the top, it narrowed down to nothing at the bottom. I went right to the bottom to maintain the best glide speed. I then pulled the plane up and landed into the side of the ravine. I didn’t travel very far at all before I hit a rock pile that caved in the nose. The instrument panel was torn out of its mounts and dropped down on my shins.

Neither of my passengers was hurt, but there was one fatality. We ran over a rattlesnake with the belly of the airplane when the gear tore out from under it.

We sat there awaiting rescue. I considered what had caused the lack of power. Only one thing was possible: the plane had been serviced with jet fuel instead of gasoline.

To confirm my suspicions, I went around to the side of the airplane and opened the drain valve. I leaned down and took a whiff. Sure enough, it was jet fuel.

My mind flashed at once to the young man I had asked to service the airplane. He must have known by then what had happened as I had informed the tower of the emergency.

Within minutes, rescue helicopters were on the scene. My passengers and I climbed up the ravine and were transported back to Brown Field.

After making sure the Shrike would be protected from theft, I asked, “Where is the line boy who serviced the plane?”

Everyone seemed reluctant to tell me, apparently afraid that I wanted to chew him out or be unkind to him. Finally, someone said, “He’s outside.”

An article in the Fullerton (Calif.) News-Tribune the next day quoted me regarding what happened next:

When I got back to the field, I saw the boy standing by the fence with tears in his eyes.

I went over and put my arm around him and said, “There isn’t a man alive who hasn’t made a mistake. But I’m positive you’ll never make this mistake again. That’s why I want to make sure that you’re the only one to refuel my plane tomorrow. I won’t let anyone else on the field touch it.”

Just as I said, I had the boy refuel my P-51 for the final two days of the air show. Needless to say, there were no further incidents.

Shortly after that, I received a wonderful letter from a doctor in Palos Verdes named William Snow.

He wrote:

I wanted you to know that I was quite touched by the apparent casual way in which you trea

ted your unfortunate incident. Thank goodness it was just that and nothing more! However, what really impressed me was your genuine concern for the young man who had serviced your plane.

It is rare to find a person who has just experienced such a close brush with death and yet feels such compassion for his fellow man. God surely must be your copilot!

I could have just cut off that excerpt at the part where Hoover crashed, but I was so impressed by how he treated the line boy, that I’m sure you all wanted to hear how it ended.

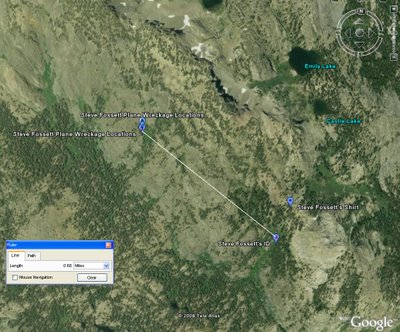

Another interesting photo is of the Google Earth map below that shows where the shirt and ID were found. They appear to be about .7 miles from the wreckage. I can only assume that those items may have gotten carried away by animals.

The NTSB report has very few details so far, but I’m sure that it will accumulate more details about the crash as they start to examine the wreckage.

We may never know what happened, but it’s obvious a fire ensued after the crash. Had the fire started while he was flying? If so, was he attempting to get the airplane on the ground as quickly as possible using the famed Hoover maneuver? We may never know, but I am eager to see what the NTSB has to say about it after they spend some time examining the wreckage.